The bird sanctuary at Bharatpur did much to thrill and satisfy; but it was with irrepressible anticipation that we finally arrived at Agra Railway Station where a visit to the Taj Mahal would be the piece de resistance of our Indian interlude. Despite the fact that the Taj is one of the world’s most visited monuments and certainly the most popular in India, the city of Agra has remained unchanged—a pockmark on a truly beauteous visage. Development has only affected the quality of hotels serving wealthy tourists—each more ostentatious than the next, more sprawling that its neighbor. In terms of infrastructure, there has been no advancement in Agra at all and the lives of the common folks appear unaffected by the nation’s recent economic prosperity.

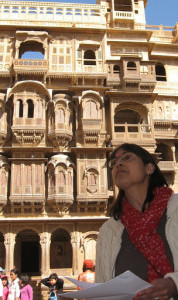

Still, the Taj apart, the city boasts some of the most significant Islamic buildings in India. The only pity is that some truly amazing examples of Islamic architectural genius, precursors of the Taj Mahal, remain neglected—such as Akbar’s Tomb at Sikhandra and Itmad-u-Daulah’s Mausoleum, the tomb build by Queen Nur Jehan for her father—both of which I fondly remember exploring as a child in the company of my parents whose enthusiasm for the treasures of their country inculcated in me an abiding love for its remnant monuments.

Introduction to Islamic Decorative Arts at The Red Fort:

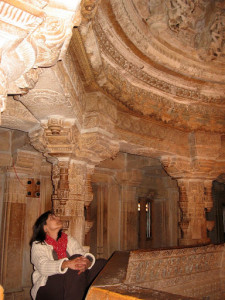

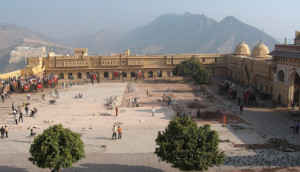

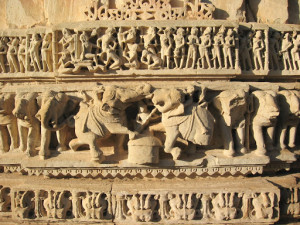

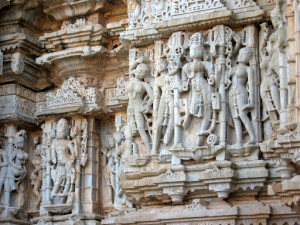

Our forays into the achievements of Islamic architecture began at the soaring Red Fort, a counterpart of the one in Delhi built by Shah Jehan. In Agra, it is Akbar who must be credited for visualizing a structure that is awesome in its dimensions and exquisite in the delicacy of its surface decoration that features bas-relief in geometric and floral forms. A conglomeration of red and yellow sandstone and grey granite, not to mention marble and stucco, added successively over several decades by astute Moghul rulers eager to carve their own niche in history, has resulted in the massive shape and form of the fortress. A micocosmic world unto itself, such complexes reflect every nuance of Moghul cultural life—from the sophistication of learned poets and talented musicians to the provocation of countless harem ladies who brought feminine wiles to play upon masculine egos and eccentricities.

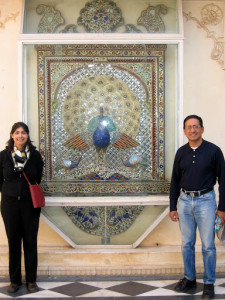

All of these contradictory impulses are evident in the Khas Mahal (above right) , for instance, with its intricate Florentine pietra dura design (above left) that overlooks the banks of the Yamuna River upon which is very poignantly outlined the purity of the Taj Mahal’s curves and curlicues (below left).

A small room with a cupola at the top (above right) indicates the space in which Emperor Shah Jehan spent the last twenty years of life, after his imprisonment by his son Aurangzeb. The fort holds moving memories of the ruthlessness that embodied Moghul supremacy at the same time that preceding reigns were tempered by mercy. Walking through the spacious courtyards that segregate one fine building from the next, one is stuck by the grandeur of the period as seen, for instance, in the huge bathing tub that was used by the ladies-in-waiting, while scented with the fragrance of rose attar (below right). How decadent, you think, was that era! How refined and yet how prosaic!

(A few of the architectural nuances of the Red Fort)

Lunch at the Oberoi Grand Hotel:

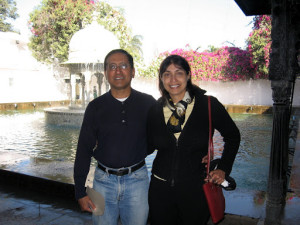

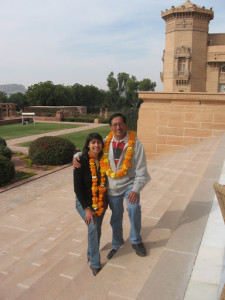

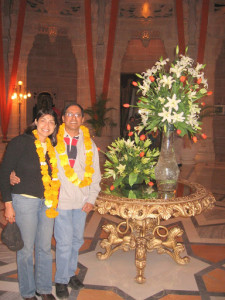

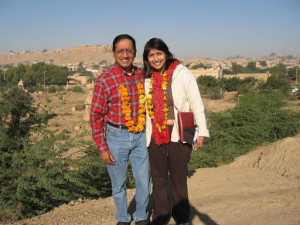

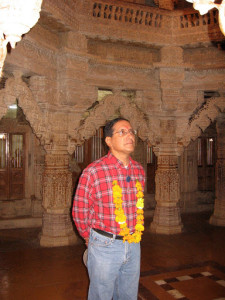

That afternoon, we lunched at one of Agra’s most opulent hotels—the Oberoi Grand. Draped withthose ubiquitous mariegold garlands, we arrived at a banquet hall for a buffet luncheon that beggars description. Every conceivable cuisine from Indian to Chinese to Continental was ours for the sampling and the desserts, stretched across three tables, were sinfully decadent. Much as I longed to linger amidst this gourmet paradise, we had to get a quick move on as the treasures of the Taj Mahal awaited and we were aflame with anticipation.

Arrival at the Taj Mahal:

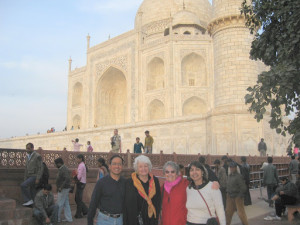

Thoughts of indulgence and excess—both among Moghul courtesans and modern-day tourists–continued to assault my mind as we arrived at the Taj Mahal. Despite the tightening of security that has altered the original entrance to the monument, there is a great and tangible thrill among one’s fellow-visitors as one enters the grand precincts of this structure. For every detail has been so carefully thought over in the planning and execution of this mausoleum that only genius could have so perfectly conceived of it.

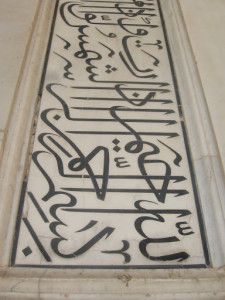

Take, for instance, the towering main gate through which one enters which so completely conceals the mausoleum from view. Decorated with black onyx inlay in marble and featuring Koranic calligraphy (left), this entrance is truly spectacular. It might be a good idea to commission one of the professional photographers to take your picture because it is almost impossible to capture images of the Taj without a thousand people in the background. Indeed, one of the things that struck me immediately was the large number of tourists that flock to this monument and the fact that most of them are Indians representing every class and region of the country.

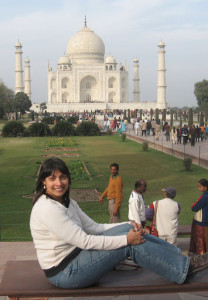

Then, suddenly, one has crossed the threshold and there, in all its stunning glory is the Taj. I remember gazing upon it for the first time in my life at age 13 and feeling my breath catch, quite literally, in my throat. I understood the meaning of the word ‘breathtaking’ in that very instant. In that respect, the effect of the Taj is similar to that of the Grand Canyon. Not all the pictures in the world can quite prepare the viewer for its impact that comes at you like a thunderbolt. It is indescribably sensational and the best way to take it in is to find a quiet spot, as I did, somewhere towards the side, far from the madding crowd, and to spend at least five minutes gazing in silence at the onion domes and the pencil-slim minarets. I let my eyes roam freely over the poetry in marble created by the combination of delicate floral tracery on the translucent walls with the contrasting red sandstone buildings that flank its sides and the gentle arches that lead one into the concealed treasures within and, believe me, in spite of myself, they filled with tears and clouded over. I have been moved to tears by movies and by exquisite pieces of classical Western music—but this is the first time in my memory that I was brought to tears merely by being in the presence of architectural beauty and magnificence.

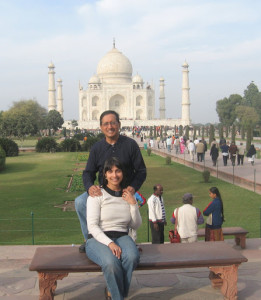

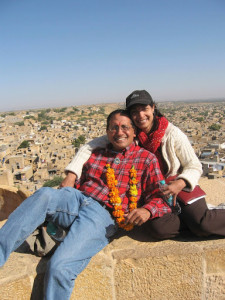

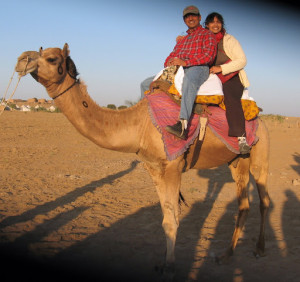

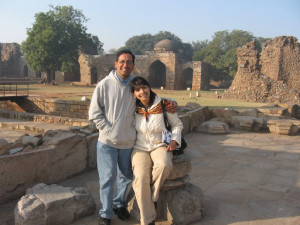

But then maybe I was moved to tears for other reasons. This location is special for us–it was at the Taj Mahal, right there on the ‘Diana Bench’–long before it became known as the ‘Diana Bench’–that Llew proposed to me and slipped the engagement ring on my finger. Yes, as he put it so eloquently, “at the world’s best-known monument to everlasting love and devotion”, we made the commitment to marry. And so, I might have been tearing up because I cannot gaze upon this poem in marble and not recall that magical day, that enchanted moment, that second that hangs suspended in my consciousness, when we hitched our fortunes together for a lifetime. Naturally, we had to take pictures again on that same bench to commemorate our date with fate.

When you have feasted your eyes on the exterior of this building, built by Emperor Shah Jehan to commemorate the life of and his love for Mumtaz, his beloved wife who died while giving birth to his fourteenth child, start to make your way along the garden path towards the main entrance. Here, it is necessary to take off your footwear or wear cloth socks over your shoes. The actual graves of the emperor and his wife are in the ground for, in accordance, with Islamic tenets, man returns to His Maker in a tiny plot of earth that is completely unadorned. The tomb that replicates the position of the grave above the ground is ornate, covered with more pietra dura inlay and surrounded by lattices or jalis expertly carved from thick sheets of non-porous marble from the Makhrana quarries of Rajasthan.

Whereas on several past visits to the Taj, I have seen faint lamps light up the artistic detail within, on my last visit in January 2008, I found it almost pitch dark inside, making it impossible for the observant visitor to admire the elegance of the designs created by the inlaying of semi-precious stones such as malachite and carnelian, turquoise and moonstone, opal and rose quartz, in the marble channels cut into the panels. Nor can one appreciate the workmanship involved in etching out Koranic scripture upon the interior walls or take in the beauty of the bas-relief in its delicate and very faithful representations of pomegranate and jasmine, irises and lilies on the marble walls. There is so much to examine and exclaim over as one encircles the marble screens that enclose the tombs that I could have stayed there all day despite the near-darkness of the interior.

But eventually, like Adela Quested in A Passage to India, I found the crowds and the noise and the dimness quite claustrophobic and it was with great relief that I made my way towards the back of the Taj to look upon the almost-dry basin of the Yamuna River and to admire the minarets up close. Any way you look at it, literally, the Taj enchants and it might be best to arrive there early in the morning, long before the crush of human bodies spoils the solemnity of the mood in which the mausoleum was conceived and constructed.

Good Bye to All That—Last Night on the Palace on Wheels:

After visiting a modern handicrafts workshop in Agra where the craftsmanship of centuries is still continued in the marble inlay work and carvings that abound in the Taj, we made our way back to the Palace on Wheels to enjoy our very last dinner on board.

Bon Voyage!